Using Antibiotics Wisely in Primary Care

Antibiotics

Using Antibiotics Wisely

It is estimated that over 90% of antibiotics are prescribed in the community. To help reduce unnecessary antibiotic use in primary care, Using Antibiotics Wisely has created resources and materials to help clinicians choose wisely in practice.

-

Don’t prescribe antibiotics in vaccinated children more than 6 months old and adults in whom you suspect acute otitis media, unless there is either a perforated tympanic membrane with purulent discharge or a bulging tympanic membrane with one of the three following criteria:

- Fever (≥39°C)

- Moderately or severely ill

- Significant symptoms lasting > 48 hours

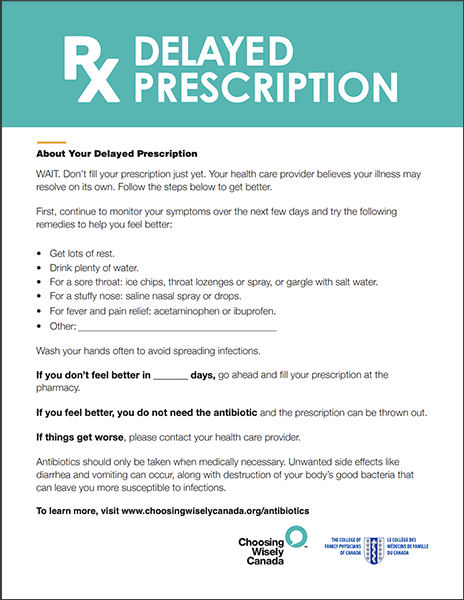

In cases that do not fit these criteria, consider either no prescription with reassessment if symptoms do not improve, or a delayed prescription approach. Don’t misinterpret patient’s or parental concern for a desire for antibiotics. Symptom control and access to follow-up if needed are often what they are looking for.

Tools to Support Practice:

Common Myths:

- All patients given a delayed prescription will take the antibiotic: only about 1 in 3 prescription gets filled

- A delayed prescription satisfies the patient more than no prescription: communication is linked to satisfaction, not prescription

- A just in case immediate antibiotic prescription is a prudent practice (there is no decrease in pain and complications with an immediate prescription; but more vomiting, diarrhea and rash)

-

Don’t routinely prescribe antibiotics unless the patient’s modified Centor score is ≥ 2 AND throat swab culture (or rapid antigen test if available) confirms presence of Group A Streptococcus.

Don’t perform throat swabs at all for patients with Centor score ≤ 1, OR if there are symptoms of a viral infection such as rhinorrhea, oral ulcers or hoarseness.

Tools to Support Practice:

Common Myth:

- Patients not receiving antibiotics will be disappointed and will seek care elsewhere: satisfaction is not linked to antibiotic prescription as many seek reassurance, information and pain relief

-

Don’t prescribe antibiotics unless symptoms have persisted for greater than 7-10 days without improvement.

Differentiating viral rhinosinusitis (VRS) from acute bacterial rhinosinusitis (ABRS) can be challenging. Patients not meeting the below criteria are best managed with a viral prescription. Antibiotics should only be considered if the patient has at least 2 of the below PODS symptoms, one of those being O or D, AND the patient meets one of the following criteria:

- The symptoms are severe

- The symptoms are mild to moderate symptoms if there is no response after a 72 hours trial with nasal corticosteroids.

P: Facial Pain/pressure/fullness; O: Nasal Obstruction;

D: Purulent/discolored nasal or postnasal Discharge; S: Hyposmia/anosmia (Smell)

Tools to Support Practice:

-

Don’t prescribe antibiotics for pneumonia unless there is objective evidence.

If access to a chest x-ray is available near your clinic, don’t routinely prescribe antibiotics for suspected pneumonia without confirming the presence of a new consolidation.

Physical examination alone, demonstrating respiratory crackles, is not sufficient to establish a diagnosis of pneumonia and initiate antibiotics in the majority of situations. Patients with no vital sign abnormalities and a normal respiratory examination are unlikely to have pneumonia and most likely don’t need a chest x-ray.

Tool to Support Practice:

-

Don’t routinely prescribe antibiotics for exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease unless there is clear increase in sputum purulence with either increase in sputum volume and/or increased dyspnea

Common Myth:

- Routine prescription of antibiotic in all COPD exacerbations will prevent complications: antibiotics only prevent complications in select COPD exacerbations populations, with the greatest benefits in ICU admitted patients

Facts:

-

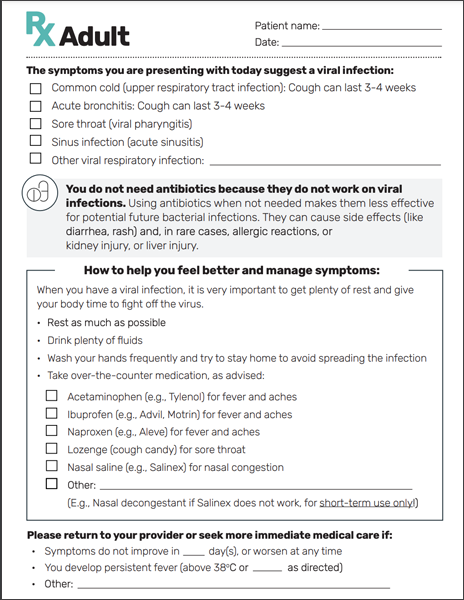

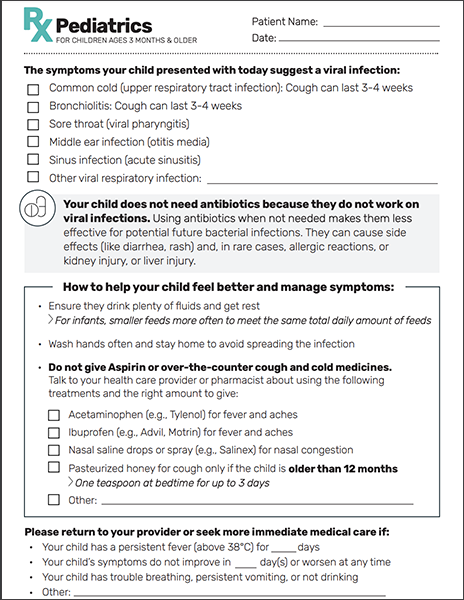

Don’t prescribe antibiotics unless there is clear evidence of secondary bacterial infection (see the recommendations for otitis media, pharyngitis, sinusitis, pneumonia).

Tools to Support Practice:

- Viral prescription pad

- General information for kids

- Information about symptoms duration (the diagram found on the CDC pamphlet might be a useful visual aid; patients may have a misconception about length of expected cough)

Common Myth:

- When patients seek a consultation for URTI symptoms it is because they want antibiotics: Information and clear instructions about symptom control will meet most patient’s expectations

-

Don’t prescribe antibiotics unless there is clear evidence of secondary bacterial infection (see the recommendations for otitis media, pharyngitis, sinusitis, pneumonia).

The use of antivirals is outside the scope of this campaign but we provide reference guidelines for clinicians to manage influenza illness in children and youth and adults. It is not recommended to test every individual meeting influenza case definition. These tests are only really useful at the beginning of an influenza season or outbreak or if they would alter management.

Tools to Support Practice:

-

Don’t prescribe antibiotics for bronchitis/asthma/bronchiolitis exacerbations.

Tool to Support Practice:

Common Myths:

- Antibiotics will prevent complications: there is no difference in clinical improvement with or without antibiotics

- My patient is still coughing after 14 days, it must be bacterial: The cough may last up to 3 weeks in 50% of patients and even more than a month for 25%

- Greenish sputum is an indication of a bacterial infection: the appearance of the sputum cannot be used to distinguish between viral and bacterial bronchitis

-

Practice Change Recommendation #1

Le Saux N, Robinson JL, Canadian Paediatric Society Infectious Diseases and Immunization Committee. Position Statement: Management of acute otitis media in children six months of age and older. Paediatr Child Health 2016;21(1):39-44.

de la Poza Abad M, Mas Dalmau G, Moreno Bakedano M, Gonzalez Gonzalez AI, Canellas Criado Y. Prescription Strategies in Acute Uncomplicated Respiratory Infections: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med 2016; 176: 21-9. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7088. PMID: 26719947.

Little P, Moore M, Kelly J, Williamson I, Leydon G et al. Delayed antibiotic prescribing strategies for respiratory tract infections in primary care: pragmatic, factorial, randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2014; 348:g1606. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1606. PMID: 24603565.

Linder JA, Singer DE. Desire for Antibiotics and Antibiotic Prescribing for Adults with Upper Respiratory Tract Infections. JGIM 2003; 18: 801. PMID: 14521641.

Mangione-Smith, R, McGlynn, E, Elliott, M, Krogstad, P, Brook, R. The Relationship Between Perceived Parental Expectations and Pediatrician Antimicrobial Prescribing Behavior. Pediatrics Apr 1999, 103 (4) 711-718; DOI: 10.1542/peds.103.4.711.PMID: 10103291.

Spurling GKP, Del Mar CB, Dooley L, Foxlee R, Farley R. Delayed antibiotic prescriptions for respiratory infections. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017, Issue 9. Art. No.: CD004417. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004417. PMID: 28881007

McKay R, Mah A, Law MR, McGrail K, Patrick DM. Systematic Review of Factors Associated with Antibiotic Prescribing for Respiratory Tract Infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60(7):4106–4118. doi:10.1128/AAC.00209-16. PMID: 27139474.

Practice Change Recommendation #2

Fine AM, Nizet V, Mandl KD. Large-scale validation of the Centor and McIsaac scores to predict group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Arch Intern Med 2012; 172(11):847–852. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.950. PMID: 22566485.

Linder JA, Singer DE. Desire for Antibiotics and Antibiotic Prescribing for Adults with Upper Respiratory Tract Infections. JGIM 2003; 18: 801. PMID: 14521641.

Mangione-Smith, R, McGlynn, E, Elliott, M, Krogstad, P, Brook, R. The Relationship Between Perceived Parental Expectations and Pediatrician Antimicrobial Prescribing Behavior. Pediatrics Apr 1999, 103 (4) 711-718; DOI: 10.1542/peds.103.4.711. PMID: 10103291.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Centre for Clinical Practice. Clinical Guideline 69: Respiratory tract infections – antibiotic prescribing. Prescribing of antibiotics for self-limiting respiratory tract infections in adults and children in primary care. 2008. Retrieved from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg69/evidence/full-guideline-196853293 (Accessed October 15, 2019)

Practice Change Recommendation #3

Gwaltney JM Jr, Wiesinger BA, Patrie JT. Acute Community‐Acquired Bacterial Sinusitis: The Value of Antimicrobial Treatment and the Natural History. Clin Infect Dis. 2004 Jan 15;38(2):227-33. PMID: 14699455.

Desrosiers M, Evans GA, Keith PK, Wright ED, Kaplan A, Bouchard J, et al. Canadian Clinical Practice Guidelines for Acute and Chronic Rhinosinusitis. Allergy, Asthma & Clinical Immunology 2011, 7:2. PMID: 21658337.

Rosenfeld RM, Piccirillo JF, Chandrasekhar SS, Brook I, Kumar KA, Kramper M, et al. Clinical practice guideline (update): Adult Sinusitis Executive Summary. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015 Apr;152(4):598-609. PMID: 25833927.

Practice Change Recommendation #4

Coxeter P, Del Mar CB, McGregor L, Beller EM, Hoffmann TC. Interventions to facilitate shared decision making to address antibiotic use for acute respiratory infections in primary care (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 11. Art. No.: CD010907. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010907.pub2. PMID: 26560888.

Linder JA, Singer DE, Stafford RS. Association between antibiotic prescribing and visit duration in adults with upper respiratory tract infections. Clin Ther 2003 Sep;25(9):2419-30. PMID: 14604741.

McKay R, Mah A, Law MR, McGrail K, Patrick DM. Systematic Review of Factors Associated with Antibiotic Prescribing for Respiratory Tract Infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60(7):4106–4118. doi:10.1128/AAC.00209-16. PMID: 27139474.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Centre for Clinical Practice. Clinical Guideline 69: Respiratory tract infections – antibiotic prescribing. Prescribing of antibiotics for self-limiting respiratory tract infections in adults and children in primary care. 2008. Retrieved from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg69/evidence/full-guideline-196853293 (Accessed October 15, 2019)

Mangione-Smith R, McGlynn EA, Elliott MN, McDonald L, Franz CE, Kravitz RL. Parent expectations for antibiotics, physician-parent communication, and satisfaction. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2001; 155(7):800–806. PMID: 11434847.

Practice Change Recommendation #5

Meeker, D, Linder JA, Fox CR, Friedberg MW, Persell SD, Goldstein NJ, Knight TK, Hay JW, Doctor JN. Effect of Behavioral Interventions on Inappropriate Antibiotic Prescribing Among Primary Care Practices: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;315(6):562-570. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.0275. PMID: 26864410.

Mangione-Smith R, McGlynn EA, Elliott MN, McDonald L, Franz CE, Kravitz RL. Parent expectations for antibiotics, physician-parent communication, and satisfaction. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2001; 155(7):800–806. PMID: 11434847.

Practice Change Recommendation #6

McKay R, Mah A, Law MR, McGrail K, Patrick DM. Systematic Review of Factors Associated with Antibiotic Prescribing for Respiratory Tract Infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60(7):4106–4118. doi:10.1128/AAC.00209-16. PMID: 27139474.

Shah SN, Bachur RG, Simel DL, Neuman MI. Does This Child Have Pneumonia?: The Rational Clinical Examination Systematic Review. JAMA. 2017 Aug 1;318(5):462-471. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.9039. PMID: 28763554.

Practice Change Recommendation #7

Stefan MS, Shieh MS, Spitzer KA et al. Association of Antibiotic Treatment With Outcomes in Patients Hospitalized for an Asthma Exacerbation Treated With Systemic Corticosteroids. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(3):333-339. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5394. PMID: 30688986.

Ebell MH, Lundgren J, Youngpairoj S. How Long Does a Cough Last? Comparing Patients’ Expectations With Data From a Systematic Review of the Literature. Ann Fam Med 2013;11:5-13. doi:10.1370/afm.1430. PMID: 23319500.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Centre for Clinical Practice. Clinical Guideline 69: Respiratory tract infections – antibiotic prescribing. Prescribing of antibiotics for self-limiting respiratory tract infections in adults and children in primary care. 2008. Retrieved from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg69/evidence/full-guideline-196853293 (Accessed October 15, 2019)

Meeker, D, Linder JA, Fox CR, Friedberg MW, Persell SD, Goldstein NJ, Knight TK, Hay JW, Doctor JN. Effect of Behavioral Interventions on Inappropriate Antibiotic Prescribing Among Primary Care Practices: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;315(6):562-570. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.0275. PMID: 26864410.

Practice Change Recommendation #8

El Moussaoui R, Roede BM, Speelman P, Bresser P, Prins JM, Bossuyt PM. Short-course antibiotic treatment in acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis and COPD: a meta-analysis of double-blind studies. Thorax. 2008; 63:415–422. PMID: 18234905.

Falagas ME, Avgeri SG, Matthaiou DK, Dimopoulos G, Siempos II. Short- versus long-duration antimicrobial treatment for exacerbations of chronic bronchitis: a meta-analysis. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2008; 62: 442–450. PMID: 18467303.

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. GOLD. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease – Updated 2016. Glob. Initiat. Chronic Obstr. Lung Dis. Inc 1–94 (2016).

National Clinical Guideline Centre. (2010) Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care. London: National Clinical Guideline Centre. PMID: 22319804.

Stockley RA O’Brien C, Pye A, Hill SL. Relationship of sputum color to nature and outpatient management of acute exacerbations of COPD. Chest. 2000; 117:1638–1645. PMID: 10858396.

Vollenweider DJ, Frei A, Steurer‐Stey CA, Garcia‐Aymerich J, Puhan MA. Antibiotics for exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2018, Issue 10. Art. No.: CD010257. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010257.pub2. PMID: 30371937.

Walters JAE, Tan DJ, White CJ, Gibson PG, Wood-Baker R, Walters E. Systemic corticosteroids for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014, Issue 9. Art. No.: CD001288. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001288.pub4Quon et al. Contemporary management of acute exacerbations of COPD: A systematic review and metanalysis. Chest 2008; 133:756–766. PMID: 25178099.https://choosingwiselycanada.org/download/3564

Sources:

About Choosing Wisely Canada

Choosing Wisely Canada is the national voice for reducing unnecessary tests and treatments in health care. One of its important functions is to help clinicians and patients engage in conversations that lead to smart and effective care choices.

Web: choosingwiselycanada.org

Email: info@choosingwiselycanada.org

Twitter: @ChooseWiselyCA

Facebook: /ChoosingWiselyCanada

The "Sorry" Poster

Available in: English | Arabic | French | Chinese (Simplified) | Punjabi | Spanish | Tagalog

The "Three Questions" Poster

Available in: English | Arabic | French | Chinese (Simplified) | Punjabi | Spanish | Tagalog

The Cold Standard

A toolkit for using antibiotics wisely for the management of respiratory tract infections.

Antibiotics for Ear Infections in Children

When you need them and when you don’t.

Navigating Colds, Flu, and Kids

Don’t rush to antibiotics.

Antibiotics for Urinary Tract Infections in Older People

When you need them and when you don’t.

Colds, Flu, and Other Respiratory Infections

Don't rush to antibiotics.

Bronchiolitis

What it means and how you can help your child.